-

Internal audit

In today's increasingly competitive and regulated market place, organisations - both public and private - must demonstrate that they have adequate controls and safeguards in place. The availability of qualified internal audit resources is a common challenge for many organisations.

-

IFRS

At Grant Thornton, our International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) advisers can help you navigate the complexity of financial reporting so you can focus your time and effort on running your business.

-

Audit quality monitoring

Having a robust process of quality control is one of the most effective ways to guarantee we deliver high-quality services to our clients.

-

Global audit technology

We apply our global audit methodology through an integrated set of software tools known as the Voyager suite.

-

Looking for permanent staff

Grant Thornton's executive recruitment is the real executive search and headhunting firms in Thailand.

-

Looking for interim executives

Interim executives are fixed-term-contract employees. Grant Thornton's specialist Executive Recruitment team can help you meet your interim executive needs

-

Looking for permanent or interim job

You may be in another job already but are willing to consider a career move should the right position at the right company become available. Or you may not be working at the moment and would like to hear from us when a relevant job comes up.

-

Practice areas

We provide retained recruitment services to multinational, Thai and Japanese organisations that are looking to fill management positions and senior level roles in Thailand.

-

Submit your resume

Executive recruitment portal

-

Update your resume

Executive recruitment portal

-

Available positions

Available positions for executive recruitment portal

-

General intelligence assessments

The Applied Reasoning Test (ART) is a general intelligence assessment that enables you to assess the level of verbal, numerical reasoning and problem solving capabilities of job candidates in a reliable and job-related manner.

-

Candidate background checks

We provide background checks and employee screening services to help our clients keep their organisation safe and profitable by protecting against the numerous pitfalls caused by unqualified, unethical, dangerous or criminal employees.

-

Capital markets

If you’re buying or selling financial securities, you want corporate finance specialists experienced in international capital markets on your side.

-

Corporate simplification

Corporate simplification

-

Expert witness

Expert witness

-

Family office services

Family office services

-

Financial models

Financial models

-

Forensic Advisory

Investigations

-

Independent business review

Does your company need a health check? Grant Thornton’s expert team can help you get to the heart of your issues to drive sustainable growth.

-

Mergers & acquisitions

Mergers & acquisitions

-

Operational advisory

Grant Thornton’s operational advisory specialists can help you realise your full potential for growth.

-

Raising finance

Raising finance

-

Restructuring & Reorganisation

Grant Thornton can help with financial restructuring and turnaround projects, including managing stakeholders and developing platforms for growth.

-

Risk management

Risk management

-

Transaction advisory

Transaction advisory

-

Valuations

Valuations

-

Human Capital Consulting

From time to time, companies find themselves looking for temporary accounting resources. Often this is because of staff leaving, pressures at month-end and quarter-end, or specific short-term projects the company is undertaking.

-

Strategy & Business Model

Strategy & Business Model

-

Process Optimisation & Finance Transformation

Process Optimisation & Finance Transformation

-

System & Technology

System & Technology

-

Digital Transformation

Digital Transformation

-

International tax

With experts working in more than 130 countries, Grant Thornton can help you navigate complex tax laws across multiple jurisdictions.

-

Licensing and incentives application services

Licensing and incentives application services

-

Transfer pricing

If your company operates in more than one country, transfer pricing affects you. Grant Thornton’s experts can help you manage this complex and critical area.

-

Global mobility services

Employing foreign people in Australia, or sending Australian people offshore, both add complexity to your tax obligations and benefits – and we can guide you through them.

-

Tax compliance and tax due diligence review services

Tax compliance

-

Value-Added Tax

Value-Added Tax

-

Customs and Trade

Customs and Trade

-

Service Line

グラントソントン・タイランド サービスライン

-

Business Process Outsourcing

Companies, large and small, need to focus on core activities. Still, non-core activities are important, and they need to be leaner and more efficient than most companies can make them sustainably. For Grant Thornton, your non-core activities are our core business. Grant Thornton’s experienced outsourcing team helps companies ensure resilience, improve performance, manage costs, and enhance agility in resourcing and skills. Who better to do this than an organisation with 73,000 accountants? At Grant Thornton we recognise that that outsourcing your F&A functions is a strategic decision and an extension of your brand. This means we take your business as seriously as we take our own.

-

Technology and Robotics

We provide practical digital transformation solutions anchored in business issues and opportunities. Our approach is not from technology but from business. We are particularly adept at assessing and implementing fast and iterative digital interventions which can drive high value in low complex environments. Using digital solutions, we help clients create new business value, drive efficiencies in existing processes and prepare for strategic events like mergers. We implement solutions to refresh value and create sustainable change. Our solutions help clients drive better and more insightful decisions through analytics, automate processes and make the most of artificial intelligence and machine learning. Wherever possible we will leverage your existing technologies as our interest is in solving your business problems – not in selling you more software and hardware.

-

Technical Accounting Solutions

The finance function is an essential part of the organisation and chief financial officer (CFO) being the leader has the responsibility to ensure financial discipline, compliance, and internal controls. As the finance function is critical in every phase of a company’s growth, the CFO role also demands attention in defining business strategy, mitigating risks, and mentoring the leadership. We offer technical accounting services to finance leaders to help them navigate complex financial and regulatory environments, such as financial reporting and accounting standards, managing compliance requirements, and event-based accounting such as dissolutions, mergers and acquisitions.

-

Accounting Services

Whether you are a local Thai company or a multinational company with a branch or head office in Thailand you are obliged to keep accounts and arrange for a qualified bookkeeper to keep and prepare accounts in accordance with accounting standards. This can be time consuming and even a little dauting making sure you conform with all the regulatory requirements in Thailand and using Thai language. We offer you complete peace of mind by looking after all your statutory accounting requirements. You will have a single point of contact to work with in our team who will be responsible for your accounts – no matter small or large. We also have one of the largest teams of Xero Certified Advisors in Thailand ensuring your accounts are maintained in a cloud-based system that you have access to too.

-

Staff Augmentation

We offer Staff Augmentation services where our staff, under the direction and supervision of the company’s officers, perform accounting and accounting-related work.

-

Payroll Services

More and more companies are beginning to realize the benefits of outsourcing their noncore activities, and the first to be outsourced is usually the payroll function. Payroll is easy to carve out from the rest of the business since it is usually independent of the other activities or functions within the Accounting Department. At Grant Thornton employees can gain access to their salary information and statutory filings through a specialised App on their phone. This cuts down dramatically on requests to HR for information by the employees and increases employee satisfaction. We also have an optional leave approval app too if required.

-

IBR Optimism of Thailand Mid-Market Leaders Suggests Potential Underestimation of Challenges Ahead: International Business Report, Q1 2024Bangkok, Thailand, April 2024 — The Grant Thornton International Business Report (IBR) for Q1 2024 unveils a strikingly optimistic outlook among Thailand's mid-market business leaders, juxtaposed with the looming challenges that will shape the nation's economic future. With a Business Health Index score of 13.5, Thailand outperforms its ASEAN, Asia-Pacific, and global counterparts, signaling a robust confidence that may overshadow critical issues such as demographic changes, skills shortages, and the necessity for digital advancement.

IBR Optimism of Thailand Mid-Market Leaders Suggests Potential Underestimation of Challenges Ahead: International Business Report, Q1 2024Bangkok, Thailand, April 2024 — The Grant Thornton International Business Report (IBR) for Q1 2024 unveils a strikingly optimistic outlook among Thailand's mid-market business leaders, juxtaposed with the looming challenges that will shape the nation's economic future. With a Business Health Index score of 13.5, Thailand outperforms its ASEAN, Asia-Pacific, and global counterparts, signaling a robust confidence that may overshadow critical issues such as demographic changes, skills shortages, and the necessity for digital advancement. -

Workshop Corporate Strategy and Company Health Check WorkshopThroughout this workshop, we will delve into the life cycle of companies, examining the stages of growth, maturity, and adaptation. Our focus will extend to the current business environment, where your Company stands today, and how our evolving strategy aligns with the ever-changing market dynamics.

Workshop Corporate Strategy and Company Health Check WorkshopThroughout this workshop, we will delve into the life cycle of companies, examining the stages of growth, maturity, and adaptation. Our focus will extend to the current business environment, where your Company stands today, and how our evolving strategy aligns with the ever-changing market dynamics. -

Tax and Legal update 1/2024 Introducing the New “Easy E-Receipt” Tax scheme with up to THB 50,000 in Tax DeductionsThe Revenue Department has introduced the latest tax scheme, the “Easy E-Receipt”, formerly known as “Shop Dee Mee Kuen”. This scheme is designed to offer individuals tax deductions in 2024.

Tax and Legal update 1/2024 Introducing the New “Easy E-Receipt” Tax scheme with up to THB 50,000 in Tax DeductionsThe Revenue Department has introduced the latest tax scheme, the “Easy E-Receipt”, formerly known as “Shop Dee Mee Kuen”. This scheme is designed to offer individuals tax deductions in 2024. -

TAX AND LEGAL Complying with the PDPA – A Balancing ActOrganisations must be aware of the circumstances in which they are allowed to collect data to comply with Thailand’s Personal Data Protection Act.

TAX AND LEGAL Complying with the PDPA – A Balancing ActOrganisations must be aware of the circumstances in which they are allowed to collect data to comply with Thailand’s Personal Data Protection Act.

In part 1, we discussed the ways in which Thailand’s current import duty exemption policies for low-priced goods give significant advantages to certain types of international e-commerce businesses, at the expense of local retailers.

In the final part of this article, we continue our examination of how customs rules for free trade agreements (“FTAs”) should be modernised to meet the needs of a digital economy. We will begin our analysis with a general overview of how FTAs function to foster trade amongst participant countries. Thereafter, we will see how the existing customs rules underlying FTAs work (or don’t work), and how the rules could be improved to meet the commercial realities of modern e-commerce.

FTAs are bilateral or multilateral trade deals that are aimed at liberalising trade in goods and services amongst participant countries. The 21st century saw FTAs growing globally at a historically unprecedented pace. In 2000, the World Trade Organisation (“WTO”) recorded 28 FTAs worldwide. By the end of the decade, in 2010, there were 142 FTAs. The trend continues to this very day. By 2017, the number of FTAs nearly doubled to 221 (1). This proliferation was rooted in the lack of progress of the WTO’s trade negotiations in the 1990s, which saw countries opting to enter into trade deals on bilateral and regional levels.

It was in the 1990s that ASEAN countries entered into the ASEAN free trade agreement – also known as “AFTA” – which remains a hallmark regional FTA in Southeast Asia to this day. ASEAN countries such as Thailand followed up by aggressively negotiating trade deals with key non-ASEAN trading partners. Thailand entered into 7 bilateral FTAs between 2000 – 2015. At the ASEAN level, Thailand was also party to ASEAN multilateral FTAs that included Australia, New Zealand, China, India, Japan and South Korea.

FTAs in theory and in practice

The objective of an FTA is to promote trade between participant countries by providing preferential treatment to the goods or services originating from the participant countries. We take the example of the free trade agreement between Thailand and Japan – commonly referred to as the “JTEPA” – as a case in point. Under the JTEPA, headphones from Japan may be imported into Thailand without any import duties. This is an advantageous trade term for Japanese goods since Thailand normally imposes an import duty rate of 10% on headphones. Thus, Japanese headphones have a landed-cost in Thailand that is 10% cheaper than competitors from countries such as the USA, UK or Germany.

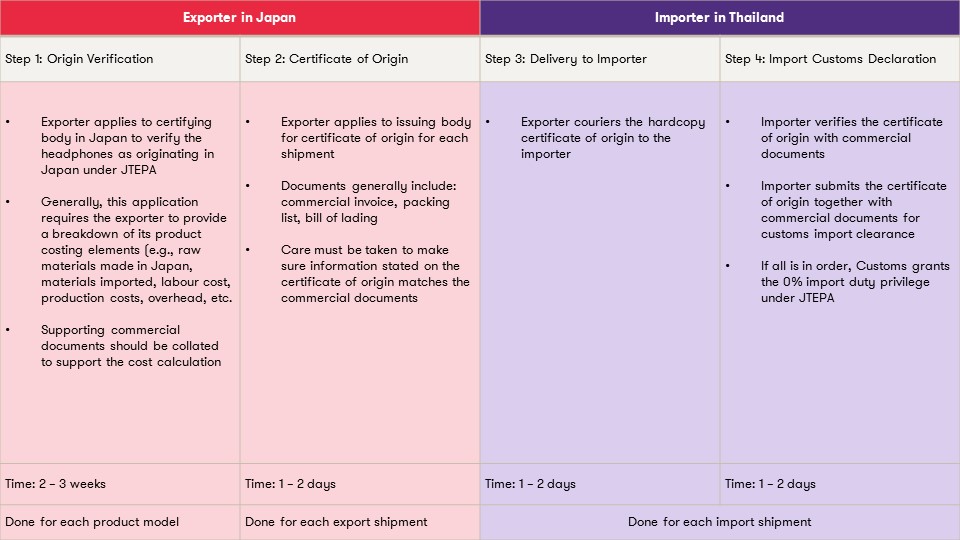

The key for Japanese headphone manufacturers to achieve this trade advantage is to ensure that its products comply with the “rules of origin” prescribed under JTEPA. That is to say, in order to qualify, the headphones must be deemed as originating from Japan. As one may expect, the devil is in the details. The process and procedures can be complex and tedious. They require an origin verification in Japan, as well as a certificate of origin, to be issued. This process must be repeated by the Japanese exporter for each product model and each export shipment.

We provide a visualisation of the process below:

As we can see, the process is still fundamentally a manual one. It takes weeks before a product’s origin can be verified. Thereafter, a physical certificate of origin must be issued. The Japanese exporter needs to courier this document overnight to the importer in Thailand. The importer takes the document and uses it for import customs clearance.

While the process is cumbersome, it was viable in an era where goods are normally shipped in bulk by ocean-going vessels. It normally takes about 1 week for goods to be shipped from Japan to Thailand, providing plenty of lead time for the critical certificate of origin to travel by air to Thailand. One certificate of origin is adequate for one shipment that could consist of 10,000 headphones imported by a wholesaler.

Now, let’s re-impose this same set of procedures for the modern e-commerce landscape and see how it works. Imagine that the Japanese exporter now must fulfil orders for 100 headphones every day. Each pair of headphones will be shipped via express airfreight and earmarked for delivery to the doorstep of the end-customer.

In order to qualify for JTEPA 0% import duty into Thailand, the Japanese exporter must apply for 100 certificates of origin every day. These documents must be couriered in time for the headphones to be declared through customs in Thailand. The importer in Thailand is no longer a single wholesaler, but 100 individual customers who are unlikely to have any knowledge of what JTEPA is or how to utilise the JTEPA import duty privilege.

In reality, the e-commerce operators will usually opt to forgo using JTEPA and simply pay the 10% import duty, or the customers in Thailand will have to pay for the 10% import duty on the goods. Thus, we see how the existing customs rules in the context of FTAs don’t work very well in this scenario.

How should customs rules for FTAs be modernised to remain relevant for the digital economy?

In part 1 of this article, we discussed the possibility of creating a higher value range for air couriered goods to be imported duty free, along with simplified customs declarations to address the problem. While these proposals may alleviate key difficulties surrounding goods that are low ticket items, they are nevertheless inadequate to solve other issues. There is still a need to improve the procedural efficiencies for higher valued goods and address the possibility that customs duties may be imposed on digital products (2).

In short, we still must develop systemic solutions to improve the efficiency of customs rules so that they allow for the principle objective of FTAs to be realised: liberalising trade between countries.

To be sure, technological innovation has made this problem more complex – but it can also provide the path to a real solution. To place Thailand at the competitive forefront of a digital economy, the government should consider harnessing digital technology in the customs administrative process. FTAs are ripe candidates for piloting and launching such technologies, as such efforts could be tried first on a smaller scale – between two, or perhaps a handful of trading partners – instead of an immediate and wholesale change to the entire system.

For instance, Thailand could opt to re-negotiate with FTA partners on adopting new systems to improve customs processes for goods traded between their countries. A new model might involve:

- Allowing manufacturers of products in a country to self-certify the products after having completed origin verification with the authorities. The self-certification declaration could be affixed to the commercial invoice accompanying the goods, or sent electronically to the importer;

- Creating an origin authentication procedure that could be linked to barcodes or QR codes on the product, whereby the self-certification could be verified to the manufacturer’s confirmed inventory, thereby preventing fraud;

- Harnessing digital technologies such as blockchain to ensure that the origin authentication data could not be manipulated, double entried, or falsified and ensuring that the data could be matched between the exporting customs authority, the importing customs authority, the exporter and the importer.

Such forward-looking initiatives would need to be implemented carefully to ensure smooth adoption and operation, but they are a necessary step towards reforming an institution that is already overdue for modernisation. As the world conducts more and more of its business online, and as Thailand embraces its vision of an advanced 4.0 economy, the Thai Customs Department should follow suit to facilitate fast, free and fair trade in the spirit of the FTAs on which the global economy now depends.

(1) Source: Asian Development Bank (ADB), Asian Regional Integration Center.

(2) As digital products such as mobile phone applications and software are now being traded across boundaries via internet and wireless download, countries are starting to consider treating such digital downloads as imports and subject to import duties. Refer to our article, Is Time Running Out for Unregulated International Software Sales? published on 7 May 2018, for more detailed discussion.