Thailand may soon join several countries in taxing digital services and products that are provided by foreign e-commerce operators.

In July 2018, the Thai Cabinet approved of a draft law that, if enacted, will see Thailand imposing value added tax (“VAT”) on foreign operators that provide services and content through the internet or electronic media to Thai consumers.[1] The Cabinet’s endorsement of the draft is the first step in the formal legislative process. From here, the draft law will be vetted by the Council of State and subsequently reviewed, and then – likely – voted into law by the National Legislative Assembly.

Once enacted, Thailand will collect VAT on various digital services and content delivered via foreign platform to Thai consumers. Taxable parties may include foreign based websites or software developers that provide on-line streaming or downloadable music and movies, on-line advertising, on-line games, on-line hotel or travel reservations, etc. This new tax law aims to plug the perceived “tax gap” by creating collection and enforcement mechanisms on business-to-consumer (“B2C”) transactions. Business-to-business (“B2B”) transactions are already subject to tax under existing VAT system.

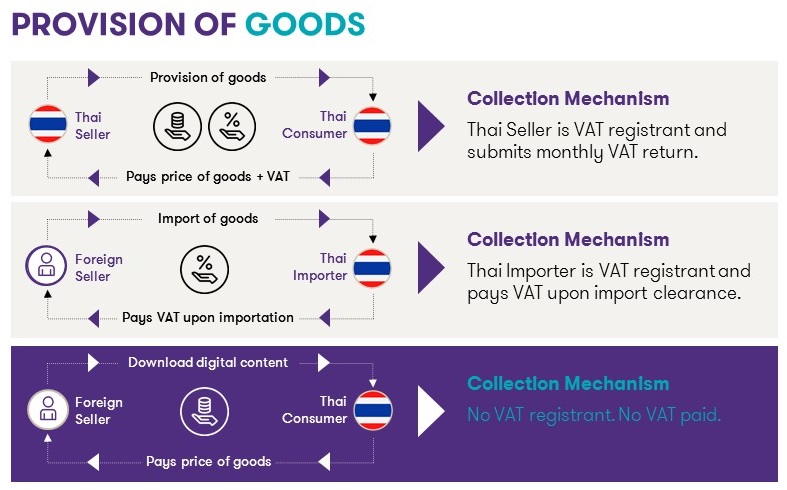

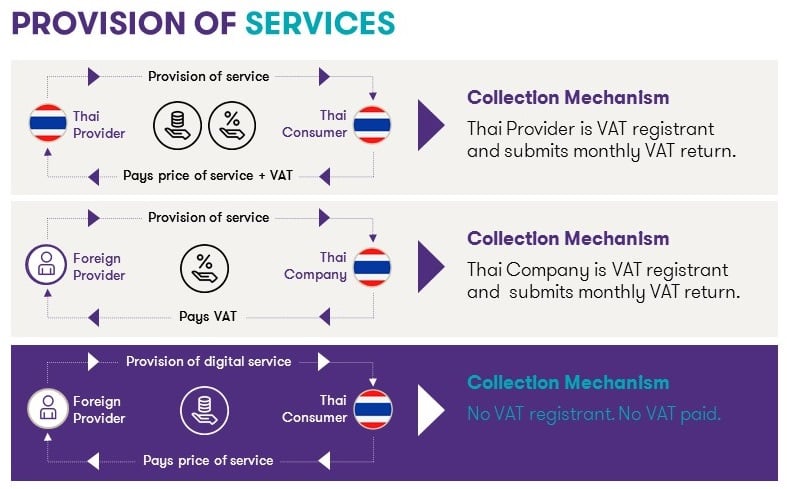

A simple illustration of the existing VAT landscape will help the reader visualise the issues succinctly.

Figure 1: Existing VAT System on Provision of Goods

Figure 2: Existing VAT System on Provision of Services

Figures 1 and 2 summarise the existing VAT regime.[2] Thailand imposes VAT on the provision of goods and services. Where the goods or services are provided by Thai sellers or providers, the Thai consumer pays for VAT together with the price of goods or services. Thai sellers or providers are required to file monthly VAT returns to the Revenue Department and submit the collected net VAT.

In the instances where goods or services are supplied by a foreign entity, the obligation to pay VAT rests on the Thai purchaser. The current law envisions that goods have to be physically imported and pass customs clearance, at which point the Customs Department will collect VAT on the imported goods. With respect to services, where the services are consumed by the Thai purchaser, the Thai purchaser who is a VAT registrant (e.g., a company) has an obligation to file a VAT return for foreign payment of services to the Revenue Department, and submit VAT on the service fee.

Designed during an era where high valued services are generally supplied in a B2B context, the tax system was tailored to capture VAT on foreign supplied B2B transactions. Taxing B2C transactions was deemed inefficient – the value is too low to justify the cost of collection. However, with the advent of digital commerce and the explosion of B2C service transactions, the tax gap with respect to foreign supplied B2C transactions becomes more glaring (and economically justified from a cost vs. collection perspective).

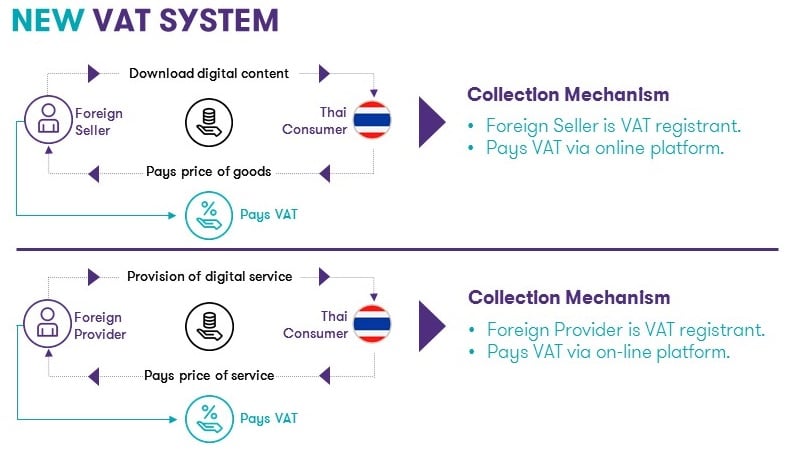

Figure 3 depicts how the Thai government intends to “re-capture” VAT at the foreign supplied B2C level.

Figure 3: New VAT System on the Digital Economy

For many foreign e-commerce operators, Thailand’s attempt to tax the digital economy should come as no surprise. Recent years have seen many countries expanding or in the process of expanding their tax net to capture digital transactions – especially those transactions that cross national or state boundaries.

As with Thailand, tax systems in many other countries were also written prior to the growth of the digital economy. Transaction taxes such as general sales tax (“GST”), consumption tax, VAT or customs duties are written from the perspective that businesses are transacted through physical movements of goods or persons, or physical presences. However, as national boundaries and physical presence are irrelevant in a digital economy, traditional tax collection mechanisms were left obsolete.

Given that traditional tax systems are unable to capture the taxable profits or revenues generated in a digital economy, new tax systems must be developed to plug the tax gap in order to avoid the loss of tax revenue. Such a tax system will also serve to create a level playing field for both traditional and digital business operators.

At the time of this writing, Australia, Argentina, some countries in the European Union, Japan, Korea, Canada, Singapore, Taiwan, New Zealand, and some states in the United States of America have either implemented taxes on the digital economy or have plans to implement new tax systems. In the next part of our article, we will discuss in further detail the trends and developments in digital commerce tax across various countries.

[1] Nation Multimedia, VAT on E-Commerce, Internet Platforms, 18 July 2018, http://www.nationmultimedia.com/detail/Economy/30350265.

[2] From a legal perspective, it is still an open question whether digital content (i.e., intangible goods) should be deemed goods or services. For more discussion on this matter, refer to our article. For our current purposes, we apply the layman’s view that intangible goods are goods. From the VAT perspective, there is no material impact – both goods and services are subject to VAT.